The English Civil War: 1625--1660

The Period

|

Though only covering the short period of time between 1625 (upon the death of James I) to 1660 (the restoration of the monarchy) this stormy political era produced many important British writers. The death of King Charles I, who was publicly beheaded in London, was one of many traumatic events that shaped the growth of the British empire. |

|

|

The English Civil War (Scots fought too) was based on a combination of political and religious issues, far too complex to cover here in much detail. In a simplistic summary, Puritans objected to the corruption of the national church (Anglican or Church of England), and they went to war when the king closed Parliament. |

|

Parliament had long objected to the king’s behavior and his alliance with the Catholic factions from France, including his wife, a French princess and Catholic. The Puritans, along with wanting church reform, also wanted a stronger republican government, so they sought to limit the king’s power. War was inevitable. |

|

|

Early in the civil war, the Cavailers (the king’s men) held the advantage and won most of the encounters. Eventually, though, the sheer numbers of the Puritans brought advantage to the opposition; and the Puritans, led by Oliver Cromwell, turned the tide of the war. In time, the entire royal court was sent to France or safety. |

|

After the king was captured and killed, in 1642, the Puritans maintained control over England and Scotland, under the leadership of Cromwell, as “Lord Protector.” The dead king’s son, Charles, was crowned as Charles II in France. He and the royal court waited for a time when England and Scotland would want a king again. |

|

|

Eventually, Cromwell died and his son became the new “Lord Protector.” The British people longed for a return of the Cavalier tradition as they tired from Puritan reformation and social constraints. In the “Restoration” of 1660, Charles II returned to England as king, ending the civil war period. However, the issues would rise again in 1688. |

John Donne

|

John Donne was the chief name among the Metaphysical poets, those who stayed out of politics and wrote about philosophy and the meaning of life. Donne was a Catholic who converted and became an Anglican minister. His work, though popular within his social circle, was not considered as important literature until the 20th century. |

|

|

"Song" is about a man who doesn’t want his wife to “worry herself to death” every time he is forces to take a trip somewhere. He tells her, in a nice way, that eventually he’s going to die, so she might as well get used to the idea. The poem had a nice blend of sincerity and humor. |

|

"Holy Sonnet 10" or “Death be not proud...” builds the argument that Death is nothing for man to fear. Death is no more than a servant, one who performs his duties by following orders. Donne concludes that once his duty is done, Death “dies” and man lives on forever. |

|

|

"Holy Sonnet 14" deals with Donne’s relationship with God. He feels that he would be better off as God’s slave, without the temptation that comes from free will. Man loves God (wants to be good) but is betrothed to Satan (performs selfish deeds). Also, “reason” is shown as God’s gift which is corrupted by man. |

| "Meditation 17" is one of the most famous sermons ever written. The theme deals with the belief that the church is the body and its members all gain or lose according to the fate of the church. Since “no man is an island,” the church’s death bell rings not for the dead man, but for the whole congregation. |

|

George Herbert

| George Herbert was another Anglican minister who chose to be a metaphysical poet. Herbert was very serious about his religion, almost to the point of obsession. His writing was not intended for publication. |

|

Because of poor health, Herbert rendered little value to his “earthly” life and looked forward to the afterlife. His verse is marked by quietness of tone, precision of language, metrical versatility, and the use of conceits.

|

|

”Man” develops man’s body as God’s prefect creation. Herbert says that God built this palace to dwell in. Thus, if man allows God to live within, he will live with God in the next life. |

|

| "Easter Wings" is a set of verses that deal with a “death” and “resurrection” theme that is the basis for the Easter celebration. Man will fall in sin or failing health and rise up with God’s help. |

|

"Easter Wings" is a special kind of poem called an emblematic image, a poem that shows the physical shape of what it’s supposed to represent. If turned on the side, the poem may look like the wings of two angels. |

|

"Virtue" says that all things of the earth will die except the virtuous soul. Using a conceit for treated wood, Herbert says that virtue preserves the soul, allowing it eternal life, unlike any other element. |

|

Ben Jonson

| Ben Jonson was the only important playwright of the civil war era, but he should be remembered as a leader of the Cavalier literary movement, following in the Shakespearean tradition. Though Puritans controlled England during most of the civil war period, the “Sons of Ben” were the best known poets. |

|

|

"On My First Son" is an autobiographical poem about the loss of a child. The morality rate was very high in Jonson’s time, so parents should have been prepared for a child’s death. Jonson, however, placed so much love upon his first son that his loss was completely heart-breaking. |

| "Song: to Celia" is a love-song taken from a play. It’s nothing more than hyperbole sung to praise the great worth of its subject, Celia. The singer claims that Celia’s kiss is better than the nectar of the gods and her beauty is so great that it would prolong the life of flowers. |

|

|

"To the Memory of My Beloved Master William Shakespeare" was Jonson’s highest praise for the “Bard.” Shakespeare had actually acted in some of Jonson’s plays. Jonson believed that Shakespeare outshined any writer, ancient or modern, and that Shakespeare deserved a special a special tomb, apart from England’s other writers. |

| "Still to be Neat" is very Cavalier in spirit. Jonson claims that natural, unadorned beauty is superior to the artificial beauty produced by make-up, dress, and perfume. The cosmetic beauty appeals to his eyes, he admits; but natural beauty appeals to his heart. |

|

Robert Herrick

| Robert Herrick was an Anglican minister who served as a chaplain for the Cavalier troops of Charles I during the English Civil War. While not interested in poetry as art, Herrick wrote entertaining verse that features a simplistic, musical quality. His spirited mood and themes make him an excellent representative of the Cavaliers. |

|

|

In Herrick’s "Ode to Him," Ben Jonson is praised as a leader of the “Sons of Ben.” This poem is much more direct and simple than the elaborate poem Jonson wrote for Shakespeare. Herrick praises Jonson’s social wit, claiming that it is to be cherished because it’s impossible to replace. |

| "To the Virgins to Make Much of Time" is another seduction poem in the spirit of “Sweet and Twenty” and "To His Coy Mistress." Herrick’s advice to virgins, either male or female, is to live life fullest in youth because it’s a time that won’t last forever. “Gather ye rosebuds while ye may” implies that one should seek multiple romances.

|

|

Richard Lovelace

|

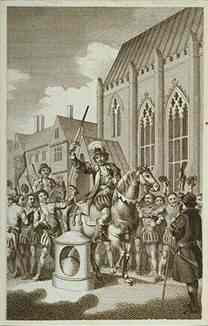

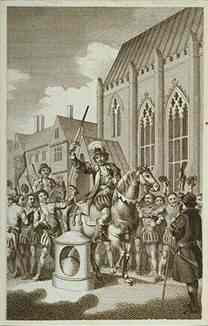

Richard Lovelace was another nobleman who fought for Charles I. He, too, lost fortune and life in the king’s defense. Lovelace is best known for the actions that put him into prison under Puritan control. He rode a white horse into the halls of Parliament, demanding the return of the king, leading to his arrest. |

|

|

"To Lucasta, on Going to the Wars" creates a unique paradox over love and honor. After telling his love that he’s leaving her for the adventures of war, he says that he could never love her unless he loved honor more. Essentially, being an honorable soldier is the only way to be worthy of her. |

|

"To Althea, from Prison" is written from within prison. Lovelace considers his freedom as a quality that is more mental than physical. He feels they may imprison his body, but his spirit will remain free. His famous lines from the concluding stanza are “Stone walls do not a prison make, Nor iron bars a cage.” |

|

John Milton

| John Milton is considered one of England’s greatest poets, chiefly because of his masterpiece Paradise Lost. Milton prospered under Puritan rule, serving as Cromwell’s chief writer, and suffered under the persecution of the restoration. |

|

If not for the intervention of Andrew Marvell, Milton might have been executed by Charles II. Instead, he went into seclusion and lost his vision. As a blind man, he recited to his daughters the poem that would bring him so much fame.

|

|

"When I Consider How My Light Is Spent" deals with Milton’s blindness. He wonders what God would demand from a blind man and concludes that all God could ever ask is that he accept God’s will and do his best, because angels also serve those “who stand and wait.” |

|